Legend, Lore and Lillian

by Marilyn Emerson Holtzer

Legends about Lillian Glaser and her legacy also abound. Most WGSL members know that the organization sprouted from a weaving class at Washington University taught by Lillian. Many are aware that she died tragically of asphyxiation late one night in her dye studio after a heated dye pot boiled over and extinguished the gas flame while she slept. Over the years, a few have even thought that she single-handedly founded the WGSL.

A teacher who is constantly learning is truly inspiring. Lillian’s students returned to her classes year after year, and they formed a guild (possibly while she was on leave of absence), which grew from a small nucleus to more than 35 members in just five years.

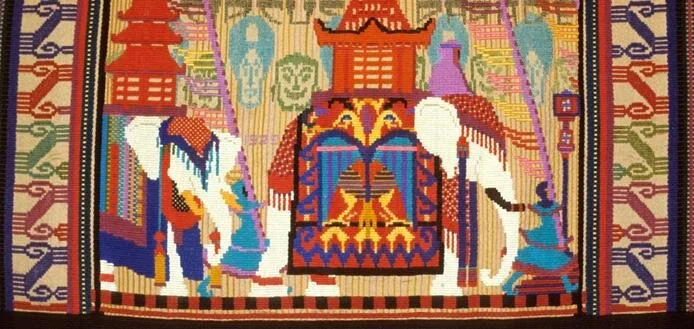

Although Lillian’s obituary describes the WGSL members as “society matrons” (and some, no doubt, were), the weavings created by Lillian and her students attest to their artistic as well as their technical competence. Their work far surpassed craft, and elevated handweaving into the realm of art. Lillian’s obituary does not actually say that she was a painter; it says only that “Her first ambition was to become a painter …” It is not known whether she painted any pictures in oil or watercolor after her school years, but it is certain that she “painted” exquisite pictures in fiber at her loom. One can only wonder how far her influence might have reached and what direction weaving in St. Louis might have taken had she not met such an untimely death.

Acknowledgement:

I wish to thank Miranda Rectenwald of the University Archives, Department of Special Collections, Washington University Libraries, for sharing her vast knowledge about the collections, for pointing me in new directions when my searches led to blind alleys, and for her willingness to retrieve any number of boxes and books.

Endnotes

1. Unknown Author, “The Weavers Guild of St. Louis: Forty Years, 1926-1966” (1966).

2. Mary K. Norton, “Second Oldest Guild in the United States,” Weavers’ Guild of Saint Louis Golden Anniversary yearbook (1975-1976).

3. Unknown Author, “A 75 Year Odyssey—Weavers’ Guild of Saint Louis”, 75th Anniversary Exhibit Brochure (2001).

4. Robert Brunkow, personal communication.

5. Hatchet (Vols. IX, XII, XIII, XV, XVI, XX) lists Lillian Glaser as a regular full-time student in the School of Fine Arts during the 1910-11, 1913-14, 1914-15, and 1921-22 academic years, and as a Saturday afternoon student in 1916-17 and 1917-18.

6. School of Fine Arts collection, WUA, 2.

7. Hatchet 1916, Vol. XIII (for 1914-1915), p. 137.

8. Hatchet 1917, Vol. XIV (for 1915-1916), p. 139.

9. School of Fine Arts collection, WUA, Financial Matters, Box 2.

10. School of Fine Arts collection, WUA, Faculty Meeting Logs (1917-1922), June 3, 1918, Box 2.

11. School of Fine Arts collection, WUA, Faculty Meeting Logs (1917-1922), May 31, 1920, Box 2.

12. Bulletin of Washington University, 53rd Annual Catalogue, Nov. 1909, p.287.

13. Hatchet 1916, Vol. XIII (for 1914-1915), p.140.

14. The Washington University Record, April 1920, Series I, Vol. XV, No. IV, p. 10.

15. Bulletin of Washington University, 63rd Annual Catalogue, Jan. 1, 1920, pp. 359, 368.

16. Hatchet 1922, Vol. XIX (for 1920-1921).

17. School of Fine Arts collection, WUA, Financial Matters, Box 2; ibid, Correspondence, Box 1.

18. Bulletin of Washington University, 1926-1927.

19. Lillian Glaser obituary, “Miss Lillian Glaser, Instructor, Found Dead in Art School, Washington U. Teacher of Weaving and Batik Asphyxiated” Student Life, May 12, 1931.

Lillian Glaser

undated

Lillian Glaser, Circus Parade, 1926

Lillian Glaser Memorial Plaque, 1931

Created by Washington University faculty member & sculptor Victor Holm. Once installed on the wall of Bixby Hall on campus, now in the collection of Missouri Historical Society.